What is an ECG?

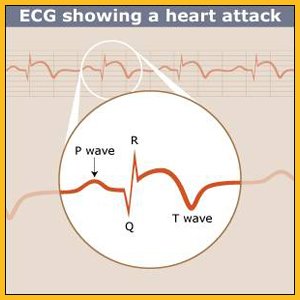

An electrocardiogram or ECG (sometimes called an EKG) is a noninvasive diagnostic test that records the heart’s electrical activity as a graph or series of wavy lines on a moving strip of paper. It records your heart rate and rhythm and can detect decreased blood flow, enlargement of the heart, and if you are having or have previously had a heart attack. You may have a resting ECG performed while you are lying down (at rest)—or an exercise ECG which is performed while you exercise (usually on a treadmill).

Who might have an ECG?

An ECG is one of the most common tests for diagnosing heart problems in women with risk factors or symptoms of heart disease. If you are suffering from chest pain, palpitations, fast or slow heart rhythms, shortness or breath, or lightheadedness, your doctor may recommend an ECG. It is one of the first tests given to someone suffering a heart attack.1

How do I prepare for an ECG?

You can eat and drink as usual. Talk to your doctor about any medications or dietary supplements you are taking because these may affect the accuracy of the test. You may have to stop taking or reduce the dosage of certain medications before the test.

What does an ECG entail?

You will remove your clothing (except your underwear) and put on a hospital gown. You will lie down and a nurse or technician will thoroughly clean 10 to 12 areas on your chest, arms, and legs. Small sticky patches will be attached to these clean areas of your skin. The patches are connected by wires to the electrocardiograph machine. You will then need to lie perfectly still for about a minute for a resting ECG. The entire ECG takes one to two minutes.

What do the results of an ECG indicate?

You should get the results immediately. A positive (abnormal) test does not necessarily mean that you have a heart problem and a negative (normal) test is not a sure sign that you are fine. If a problem is found, additional tests will probably be ordered. If no problems are found, you still may need to go for additional testing, such as an exercise ECG, or you may be asked to wear a Holter monitor, which is a portable tape recorder worn for 24 hours that records your heart’s rhythm.

Does an ECG have any limitations?

Women are prone to inconclusive tests the results aren’t clearly positive or negative. If this happens, you may be sent for further testing, such as echocardiography or a nuclear stress test. It is possible for an ECG to miss a heart problem, especially if you are not having any symptoms during the test.

ECG (Electrocardiogram) – Exercise ECG

What is an exercise ECG or stress test?

Some heart problems only show up when the heart is working hard (or stressed). An exercise ECG is a noninvasive diagnostic test that measures the heart’s electrical activity at rest and while you exercise. It is sometimes called a stress test or a treadmill test because you usually walk or run on a treadmill. This test can detect whether the heart is getting enough blood and oxygen. It also helps to determine the level of exercise that is safe for you.

Who might have an exercise ECG?

The exercise ECG is usually the first noninvasive stress test given to women with risk factors or symptoms of heart disease. Because it is easy to perform, widely available, and excellent for ruling out heart problems, this test is usually used before noninvasive imaging tests such as echocardiography and nuclear stress tests. Women older than 55 and men older than 45 who don’t work out regularly but plan to start a vigorous exercise program should have an exercise ECG to determine a safe level of exercise.2

Who should not have an exercise ECG?

If you are unable to perform physical activity due to older age, arthritis, or excess weight, you should not have an exercise ECG. In this situation, you will be sent for a noninvasive imaging test—probably echocardiography or a nuclear stress test—using a chemical that mimics the effects of exercise on the heart If you had an abnormal or inconclusive resting ECG, you will be sent for an imaging exercise test rather than an exercise ECG test. The heart medication digoxin (digitalis) can affect the accuracy of exercise ECG testing, even if you stop taking it up to 2 weeks before the test. If you are taking digoxin, you will be referred for a noninvasive imaging test instead of an exercise ECG.

How do I prepare for an exercise ECG?

You cannot smoke, eat, or drink anything other than water for three to four hours before an exercise ECG. If you have diabetes, you should discuss dietary concerns for the day of the test with your healthcare provider in order to control your blood sugar levels. Talk to your doctor about any medications or dietary supplements you are taking because these may affect the accuracy of the test. You may have to stop taking or reduce the dosage of certain medications before the test.

You should wear comfortable, loose clothing and shoes appropriate for exercising.

What does an exercise ECG entail?

You will remove your clothes from the waist up (you can keep your bra on) and wear a gown. You will lie down and a nurse or technician will thoroughly clean (and shave if necessary) 10 to 12 areas on your chest, arms, and legs. Small sticky patches will be attached to these areas of your skin. The patches are connected by wires to the electrocardiograph machine.

To determine your target heart rate, the nurse will note your age, height, weight, and what medications you currently take. You will then need to lie perfectly still for about a minute while your resting heart rate and blood pressure are measured. You will wear a blood pressure cuff for the exercise portion. You will start to exercise slowly on a treadmill or a stationary bicycle. After 3 minutes, your blood pressure is taken again. The speed and elevation of the treadmill or bicycle is increased about every 3 minutes. During the test, the doctor will speak with you and monitor your physical condition, heart rate, and ECG. You may have to wear a small mask over your mouth so that the oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the air you breathe out can be measured. The exercise portion will end when you reach your target heart rate or if you ask to stop because of fatigue or symptoms. The resting portion lasts 1 to 2 minutes. The exercise portion lasts 12 to 15 minutes.

What happens after an exercise ECG?

You can eat, drink, and resume normal activities immediately following the test. If you don’t exercise regularly, you may experience chest pain, tiredness, muscle aches, and shortness of breath afterwards. A preliminary report may be available right after the test, but the completed report usually takes a day or two.

What does a negative (normal) exercise ECG indicate?

If the test is negative (normal), you are considered to be at low risk for future heart problems such as a heart attack. A negative test also rules out the need for further invasive testing such as cardiac catheterization.

What does a positive (abnormal) exercise ECG indicate?

If you have a positive (abnormal) test, you will be sent for further testing because a positive exercise ECG alone is not enough to diagnose heart disease. If you have a positive test or one that is not clearly positive or negative, you will be referred for another type of noninvasive test such as echocardiography or a nuclear stress test.

How accurate is the exercise ECG in women?

The exercise ECG is very accurate for ruling out heart problems but it is less accurate than other noninvasive diagnostic tests for detecting heart problems. It is also less accurate in women than in men. 3, 4 Women are prone to false positive tests – the tests shows a problem but in reality there isn’t one.5 Women are also more likely to have an inconclusive test–one that is not clearly positive or negative. Female hormones can affect the test. If you still get periods, you should let the tester know what stage of your menstrual cycle you are at; if you are postmenopausal, tell them whether or not you are taking hormones. A negative (normal) test is just as reliable in women and men.

What if I feel chest pain during an exercise ECG?

During an exercise ECG, you will be asked to continue exercising until you reach your target heart rate. If you experience fatigue or symptoms before this, you can ask to stop. In men, chest pain during exercise is usually a classic sign of heart disease – a cardiac catheterization will show blockages in the arteries of the heart. However, women often experience chest pain during an exercise ECG when there are no blockages in the arteries of the heart.6 The reasons for the chest pain are not fully understood, but female hormones may play a role.

ECG (Electrocardiogram) – Response to Exercise

Apart from the ECG, what else does the exercise ECG measure?

A positive exercise ECG usually means that that there was a problem visible on the strip of paper that records the heart’s electrical activity. However, the exercise ECG measures much more than the heart’s electrical activity. It also measures your fitness level, heart rate recovery, and blood pressure response. These factors can tell a lot about your risk for future heart problems.

What is heart rate recovery and how is it related to heart disease?

Your heart rate increases during exercise and returns to normal when you stop. Heart rate recovery measures how quickly your heart rate returns to normal after you stop exercising. An abnormal heart rate recovery means that your heart rate fails to decrease by 12 or more beats per minute within the first minute after you stop exercising. Studies show that women with an abnormal heart rate recovery have a higher risk for dying in the next 5 years.7 This is true for women who have—and those who have not—been diagnosed with heart disease.8, 9 In one small study men and women who participated in a 12-week cardiac rehabilitation program improved their heart rate recovery.10

How is blood pressure in response to exercise related to heart disease?

During exercise, your systolic blood pressure (top number) should rise while your diastolic blood pressure (bottom number) should stay the same. When you stop exercising after reaching your target heart rate, your systolic blood pressure (top number) should return to its pre-test level within 6 minutes. In some people, both blood pressure numbers increase excessively during exercise. This type of exaggerated response means you have an increased risk of being diagnosed with heart disease, having a heart attack, or developing high blood pressure in the future.11, 12 It does not appear to increase your risk of actually dying from heart disease.13

How is fitness related to heart disease risk?

How fit you are is a strong indicator of your risk of dying or having a heart attack. If you are unable to exercise long enough to reach the target heart rate for a women your age, you have a higher risk of dying than a woman who can.14 In men and women with heart disease, those able to exercise longer have a much lower risk of dying than less fit patients.15

How is fitness measured?

Fitness or exercise capacity is usually measured in metabolic equivalents (METs for short). Household tasks such as stripping and making the bed require about 5 METs. If you cannot perform 5 METs of exercise, you have a 3-fold higher risk of dying or having a heart attack than a woman capable of 8 METs of exercise. For every 1 MET increase in exercise capacity, the risk of dying falls by 17%.16 Healthy women, with a below-average fitness, are over 3 times more likely to die within 20 years than women with above average-exercise capacity.17 Because the relationship between fitness and the risk of dying is so strong, some researchers suggest that treadmill testing should be included in everyone’s annual physical.

ECG (Electrocardiogram) – Risks & Limitations

Is it safe to have an exercise ECG test after a heart attack?

There is not enough safety information to justify exercise ECG testing in the first 2 to 3 days after a heart attack. It is safe to do a treadmill test more than 5 days after an uncomplicated heart attack, when stress testing can help determine a safe level of activity. A negative (normal) test means you have a low risk of having another heart attack. If you are unable to perform an exercise ECG, you are at a higher risk of having another heart attack or dying from heart disease.18, 19 You should also have an exercise ECG before starting cardiac rehabilitation or any type of exercise program.

Does an exercise ECG have any limitations?

A normal exercise ECG is a reliable test for ruling out heart problems in women. In terms of the print out showing the heart’s electrical activity, a positive exercise ECG is less reliable for women than for men. Women are prone to false positive results—the test detects a problem, but in reality there is none. Chest pain during exercise testing is also less likely to be a sign of heart disease in women than in men. Because of these limitations, you should not be referred for invasive testing such as cardiac catheterization based on a positive exercise ECG alone. The results should be confirmed through further noninvasive testing first, such as echocardiography or a nuclear stress test.

However, the exercise ECG measures a lot more than just the print out of the heart’s electrical activity. It also measures your exercise capacity, and how your blood pressure and heart rate are affected by exercise. When these factors are looked at, the exercise ECG is an excellent test for predicting your risk of having a heart attack or dying from heart disease.

References

1. Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction). 2004;Available at http://www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/1090338315100STEMIFinalFinalforposting.pdf.

2. Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Timothy Bricker J, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1531-1540.

3. Morise AP, Diamond GA. Comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of exercise electrocardiography in biased and unbiased populations of men and women. Am Heart J. 1995;130:741-747.

4. Barolsky SM, Gilbert CA, Faruqui A, Nutter DO, Schlant RC. Differences in electrocardiographic response to exercise of women and men: a non-Bayesian factor. Circulation. 1979;60:1021-1027.

5. Miller TD, Roger VL, Milavetz JJ, et al. Assessment of the exercise electrocardiogram in women versus men using tomographic myocardial perfusion imaging as the reference standard. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:868-873.

6. Alexander KP, Shaw LJ, Shaw LK, et al. Value of exercise treadmill testing in women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1657-1664.

7. Nishime EO, Cole CR, Blackstone EH, Pashkow FJ, Lauer MS. Heart Rate Recovery and Treadmill Exercise Score as Predictors of Mortality in Patients Referred for Exercise ECG. JAMA. 2000;284:1392-1398.

8. Cole CR, Blackstone EH, Pashkow FJ, Snader CE, Lauer MS. Heart-Rate Recovery Immediately after Exercise as a Predictor of Mortality. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1351-1357.

9. Cole CR, Foody JM, Blackstone EH, Lauer MS. Heart Rate Recovery after Submaximal Exercise Testing as a Predictor of Mortality in a Cardiovascularly Healthy Cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:552-555.

10. Kligfield P, McCormick A, Chai A, et al. Effect of age and gender on heart rate recovery after submaximal exercise during cardiac rehabilitation in patients with angina pectoris, recent acute myocardial infarction, or coronary bypass surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:600-603.

11. Mundal R, Kjeldsen SE, Sandvik L, et al. Exercise Blood Pressure Predicts Mortality From Myocardial Infarction. Hypertension. 1996;27:324-329.

12. McHam SA, Marwick TH, Pashkow FJ, Lauer MS. Delayed systolic blood pressure recovery after graded exercise: an independent correlate of angiographic coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:754-759.

13. Pandey DK. Exaggerated Blood Pressure Response to Exercise Predicts New-Onset Hypertension in Women: Women Take Heart Study, 1992-2001. Paper presented at: 18th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Society of Hypertension, 2003; New York.

14. Lauer MS, Francis GS, Okin PM, et al. Impaired chronotropic response to exercise stress testing as a predictor of mortality. JAMA. 1999;281:524-529.

15. Weiner DA, Ryan TJ, Parsons L, et al. Long-term prognostic value of exercise testing in men and women from the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) registry. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:865-870.

16. Gulati M, Pandey DK, Arnsdorf MF, et al. Exercise Capacity and the Risk of Death in Women: The St James Women Take Heart Project. Circulation. 2003;108:1554-1559.

17. Mora S, Redberg RF, Cui Y, et al. Ability of exercise testing to predict cardiovascular and all-cause death in asymptomatic women: a 20-year follow-up of the lipid research clinics prevalence study. JAMA. 2003;290:1600-1607.

18. Gill JB, Cairns JA, Roberts RS, et al. Prognostic Importance of Myocardial Ischemia Detected by Ambulatory Monitoring Early after Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:65-71.

19. Safstrom K, Lindahl B, Swahn E. Risk stratification in unstable coronary artery disease–exercise test and troponin T from a gender perspective. FRISC-Study Group. Fragmin during InStability in Coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1791-1800.