What is cardiac catheterization?

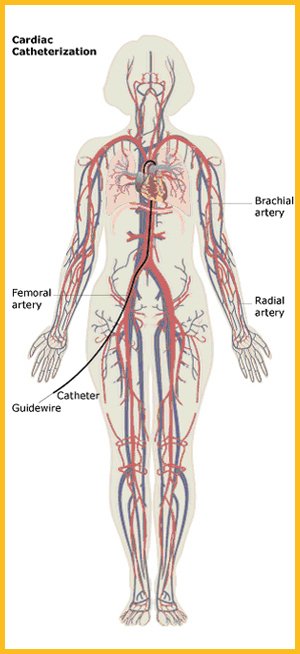

A cardiac catheterization is an invasive diagnostic test that is used to detect blockages in the arteries of the heart. The test is used to diagnose heart disease and heart attack. A long, thin tube called a catheter is inserted into an artery in your groin or forearm and a thinner tube known as a guidewire is used to guide the catheter into the various arteries of the heart. Your physician will track the course of the catheter through the blood vessels by viewing moving X-ray pictures displayed on a screen that is similar to a TV monitor. More than 1 million catheterizations are performed annually in US hospitals, and about 40% of these are in women.1

What is an angiogram?

Strictly speaking, cardiac catheterization refers only to the catheter insertion, but it is very unlikely that you will undergo cardiac catheterization without having an angiogram. The coronary angiogram is the X-ray picture of the arteries of the heart. A special dye, known as a contrast dye, is injected into the arteries that supply blood to the heart via the catheter so that the X-rays can be taken. The angiogram can be used to pinpoint the location and severity of coronary artery disease, including blocked arteries and abnormalities in the heart wall. Because it is unlikely that you will undergo cardiac catheterization without having an angiogram, the two terms are used interchangeably.

Who might have cardiac catheterization?

Cardiac catheterization is an invasive diagnostic test that is reserved for women who have a high likelihood of having heart disease or who may be having a heart attack. Up to 40% of women sent for catheterization do not show signs of blockages in their arteries.2, 3 For this reason, you will usually be sent for cardiac catheterization only after having a positive (abnormal) noninvasive test such as a nuclear stress test or echocardiogram. In an emergency situation, including a suspected heart attack, you may be sent immediately for catheterization. Cardiac catheterization helps locate the blood clot that is causing a heart attack.

Cardiac Catheterization – The Cardiac Catheterization Procedure

How do I prepare for a cardiac catheterization?

You should not eat or drink anything for about eight hours before a scheduled cardiac catheterization. If you have diabetes, you should discuss dietary concerns for the day of the test with your healthcare provider to control your blood sugar levels. Talk to your doctor about any medications or dietary supplements that you are taking because they may affect the accuracy of the test. You may have to stop taking or reduce the dosage of certain medications, particularly blood-thinning medications (such as aspirin or warfarin).

What does the test entail?

You will change into a hospital gown. The test will take place in a specialized catheterization lab; the staff wear hospital gowns and masks, and the lights are dimmed. Before the procedure, you will be asked about your medical history and you will be given blood thinners to prevent blood clots during the procedure. The physician will insert an intravenous (IV) line into your arm, so that a mild sedative and other necessary medication can be given without further injections. You may feel the needle prick when the IV is inserted. You will be hooked up to an ECG so that your heart rate can be monitored– small sticky patches with wires attached will be taped to your body. Your blood pressure will also be monitored.

Usually, the catheter is inserted via the femoral artery in your groin, but sometimes an artery in the elbow or wrist is used. The area will be cleaned, shaved if necessary, swabbed with antibacterial solution, and then numbed with a general anesthetic, which may cause a brief period of discomfort. A small cut will be made and an introducer sheath will be placed in the opening. The sheath is a short hollow tube through which the catheter is fed through the artery and into the heart. You will probably feel a warm sensation when the contrast dye is injected into the catheter. A series of X-ray pictures are taken. At times, the physician or other medical staff may ask you to cough, turn your head, or take a deep breath. You may feel some discomfort, but you should let someone know if you feel any pain. You will be awake for the entire procedure.

How long will it take?

Approximately 30 minutes to an hour. If a significant blockage is detected in the arteries of your heart that requires balloon angioplasty with or without stent treatment, you may have this procedure at the same time as your cardiac catheterization. In this instance, the procedure can take up to three hours (see Balloon angioplasty).

What happens after cardiac catheterization?

After the procedure, you will be transferred to a cardiac recovery room. You may feel groggy from the sedative, and the catheter insertion site (arm or groin) may be bruised and sore. If the groin was used as the point of catheter insertion, you will be instructed to lie in bed with your legs out straight. There are two techniques for removing the introducer sheath that was placed at the beginning of the procedure when the catheter was inserted. The more traditional method is to wait four to six hours for the effects of the blood thinners to wear off, then to apply pressure while removing the sheath. A newer technique uses a hemostatic device, such as the Angio-Seal or Perclose. These small devices are inserted to make a tiny seal or stitch in the artery to close it off. If the arm was the insertion point, you should keep your arm straight for at least one hour and you can get out of bed sooner.

Throughout the postprocedure monitoring, the point of insertion will be checked for bleeding, swelling, or inflammation, and your vital signs will be continuously monitored. You should drink plenty of fluids to flush out the contrast dye. If you feel any pain in your chest or see any bleeding at the point of insertion, tell the hospital staff immediately. You may be released on the same day or the next day with instructions from your doctor. These instructions include limiting physical activity for 24 to 48 hours, and you will be advised against driving for at least two days. Numbness and soreness are possible during the first week, and bruising can take as long as three weeks to heal.

What do the results mean?

If the angiogram shows a significant blockage in the arteries of your heart, you will need to have a procedure to clear the blockage such as angioplasty with or without stent placement or even bypass surgery. Sometimes the angioplasty and stent placement can be done at the same time as the catheterization. In other cases, it is scheduled for a future date.

Cardiac Catheterization – Risks & Limitations

What are the risks of cardiac catheterization?

Cardiac catheterization is a very safe procedure. Serious complications occur in 1% to 2% of all tests.4 Risks include bleeding around the insertion point, abnormal heartbeats, allergic reaction to the dyes used, infection, blood clots, and damage to arteries. You should tell your healthcare provider if you have had a reaction to X-ray dye, shellfish, or iodine in the past. The contrast dyes used in catheterization can also damage the kidneys in people with diabetes or previous signs of kidney damage.

Women are at a higher risk than men for bleeding problems at the catheter entry site. Removing the sheath early (with or without a device) and using lower doses of blood-thinning medications help lower the risk of bleeding problems. Some types of hemostatic sealing devices have been shown to reduce the risk of bleeding problems.5,6 When these devices are used to close the catheter entry site wound, the patient is able to get out of bed sooner and leave the hospital earlier than those treated without a device.

Cardiac catheterization involves radiation. The amount of radiation you are exposed to during cardiac diagnostic tests is considered safe. The benefits of the test far outweigh any potential risks, and the technicians are trained to minimize your radiation exposure. For information on radiation safety, see the National Institutes for Health Radiation Fact Sheet.

What are the limitations of cardiac catheterization?

Cardiac catheterization is considered the best test for diagnosing blockages in the arteries of the heart (coronary arteries). If your angiogram is clear, it is very unlikely that you have any severe blockages. An angiogram visualizes fatty blockages on the lining of the coronary arteries, but it cannot tell which ones are likely to rupture and cause a heart attack. A blocked artery is one with fatty plaque buildup that closes off more than 50% of the artery. However, a bigger blockage does not necessarily mean a higher risk of having a heart attack. Most heart attacks occur when moderately sized fatty plaques burst and a blood clot develops, closing off the artery.

Are women less likely to be sent for cardiac catheterization than men?

A 1987 study of more than 80,000 heart disease patients showed that women were less likely to undergo cardiac catheterization than men.7 However, it is not clear whether this is a case of gender bias—meaning doctors are less likely to send women for testing because they mistakenly believe that heart disease is only a problem in men—or because women do not need this test as often as men. Up to 40% of women referred for cardiac catheterization do not have significant blockages in their arteries compared with 20% of men.2,3

More recent research finds that women are just as likely as men to receive this test if you take into account their age and risk factors.8,9 Even so, a study using videotapes of actors describing identical chest pain symptoms found that the race and sex of the actor influenced the doctors decision to refer them for cardiac catheterization. Black women were less likely than white men to be referred for cardiac catheterization.10

- Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: 2004 Update. Dallas, Texas: American Heart Association; 2003.

- Kugelmass AD, Houser F, Simon A, et al. Diagnostic Results: Gender Continues to Make a Difference. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:497A.

- Roeters van Lennep JE, Zwinderman AH, Roeters van Lennep HW, et al. Gender differences in diagnosis and treatment of coronary artery disease from 1981 to 1997. No evidence for the Yentl syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:911-918.

- Bashore TM, Bates ER, Berger PB, et al. American College of Cardiology/Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions Clinical Expert Consensus Document on cardiac catheterization laboratory standards. A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:2170-2214.

- Vaitkus PT. A meta-analysis of percutaneous vascular closure devices after diagnostic catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention. J Invasive Cardiol. 2004;16:243-246.

- Koreny M, Riedmuller E, Nikfardjam M, Siostrzonek P, Mullner M. Arterial Puncture Closing Devices Compared With Standard Manual Compression After Cardiac Catheterization: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291:350-357.

- Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between men and women hospitalized for coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:221-225.

- Mark DB, Shaw LK, DeLong ER, Califf RM, Pryor DB. Absence of Sex Bias in the Referral of Patients for Cardiac Catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1101-1106.

- Wong Y, Rodwell A, Dawkins S, Livesey SA, Simpson IA. Sex differences in investigation results and treatment in subjects referred for investigation of chest pain. Heart. 2001;85:149-152.

- Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The Effect of Race and Sex on Physicians’ Recommendations for Cardiac Catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:618-626.